By Eric Nnaji [update] FILE PHOTO: Seattle Seahawks owner Paul Allen on the field before Super Bowl XLVIII against the Denver Broncos at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey, U.S., February 2, 2014. Mandatory Credit: Mark J. Rebilas/File Photo. Microsoft Corp co-founder Paul Allen, the man who persuaded school-friend Bill Gates to drop out of Harvard to start what became the world’s biggest software company, died on Monday at the age of 65, his family said. Allen left Microsoft in 1983, before the company became a corporate juggernaut, following a dispute with Gates, but his share of their original partnership allowed him to spend the rest of his life and billions of dollars on yachts, art, rock music, sports teams, brain research and real estate. Allen died from complications of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a type of cancer, the Allen family said in a statement. In early October, Allen had revealed he was being treated for the non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, ...

Katharine Murphy

So instead of being too tricky by half, and suggesting now it is marvellous we are having the inquiry, and signalling you are, of course, open to extending it, while conveniently omitting the back story – the government needs to eat crow with some humility and sincerity.

In professional politics, admitting you were wrong is the hardest thing to do, particularly in an age where the public space of politics is consumed by ad hominem insults and vicious put-downs, lobbed either by the protagonists themselves, or a chorus of onlookers chattering ceaselessly 24/7.

That’s the context sitting behind the financial services inquiry.

Admitting you were wrong is hard, but there are

bigger issues at stake now: namely whether voters can still trust institutions.

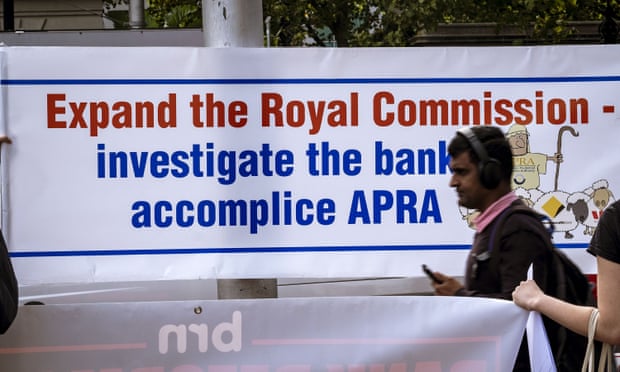

Protesters rally outside the banking royal

commission hearing in Melbourne. Photograph: Luis Ascui/EPA

Given this isn’t complicated, here’s what should

happen now.

The Turnbull government, if it has any sense of

right and wrong, and any remaining shred of political judgment, should say to

voters, without dissembling or weasel words: “Sorry, we got this one badly

wrong.”

The collective mea culpa needs to be short and

sharp, given we were all here and we all saw what happened.

We all saw the Turnbull government resist consistent

calls for a banking royal commission after a string of damaging reports about

scandals in the financial services industry. We saw that stonewalling play out

for months.

Then we saw the government forced into having an

inquiry because the prime minister and the treasurer got

overrun by restive Nationals MPs while their then leader, Barnaby

Joyce, was

trying to clean up his self-created mess on dual citizenship in the

New England byelection.

We saw Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison produce

an inquiry through gritted teeth in response to Nationals running

down the executive in full public view.

The banking royal commission has produced, in its

opening stages, ample

evidence to justify its own existence, and to validate all the news

reporting and the political advocacy from Labor, the Greens and others that

preceded its establishment.

So instead of being too tricky by half, and suggesting now it is marvellous we are having the inquiry, and signalling you are, of course, open to extending it, while conveniently omitting the back story – the government needs to eat crow with some humility and sincerity.

It is, frankly, ridiculous for senior government

figures to demand financial institutions justify their conduct while declining

to explain their own.

In professional politics, admitting you were wrong is the hardest thing to do, particularly in an age where the public space of politics is consumed by ad hominem insults and vicious put-downs, lobbed either by the protagonists themselves, or a chorus of onlookers chattering ceaselessly 24/7.

The government won’t want to hand that victory to

Labor. It won’t want to confess fallibility before the voting public,

preferring to project the sense that the emperor is still clothed.

But there are bigger issues at stake here than being

seen to capitulate, or losing a 24-hour news cycle.

What’s in play right now in Australia is trust:

whether voters can trust institutions, both private and public.

What this royal commission does is underscore the

deep concerns Australian voters have about the health of our institutions, and

whether or not our governments have the right priorities and focus.

Any politician paying attention right now will tell

you that Australian voters are in a mood, worn down by the grim circus in

Canberra, by the sense the country is drifting and political

leadership in Canberra is little more than a ghost ship; and by the nagging

sense that there was an age of prosperity and tranquility that has now been

replaced by an age of contingency and shrieking.

When many voters looks at the cadre of leaders in

this country they see politicians indulging intrigues at the expense of

meaningful progress, and businesses entirely out for themselves.

That’s the context sitting behind the financial services inquiry.

It is not happening in a vacuum.

What’s in play right now is trust, and collective

faith in representatives politics – and without it, governments have nothing.

Comments

Post a Comment